Lịch sử châu Âu/Chiến tranh thế giới thứ nhất

|

|

Trang này được dịch bằng máy từ trang gốc European History/World War I. Hãy đóng góp cho trang này bằng việc dịch lại một cách chuẩn xác hơn! |

Introduction

[sửa]As a result of German unity and increasing German nationalism, as well as various other causes, Germany began on what Kaiser Wilhelm II called a "new course" to earn its "place in the sun." After 1871, Germany's trade and industry increased vigorously, challenging and, in some areas, even exceeding that of Great Britain, until then the premier industrial nation of Europe. A many-sided rivalry developed between Germany and Britain, intensifying when the sometimes-bellicose Wilhelm II assumed power and began building a strong, ocean-going navy.

Seeking to balance the rise of German power, Britain and France began to draw closer together diplomatically as the 20th century began. Germany, meanwhile, had allowed an implicit alliance with Tsarist Russia to lapse, and faced ongoing French resentment over the provinces of Alsace and Lorraine which Germany had annexed in 1871. The perceived danger of "encirclement" by hostile nations began to loom in the minds of German leaders. These factors together formed some of the tinder which would ignite the outbreak of war in 1914.

It is interesting to note, however, that all the ruling families of Europe were related to each other in some form or fashion. This led to many Europeans feeling that it was a family affair that they had been dragged into and forced to endure.

The Road to War

[sửa]World War One is one of the most hotly contested issues in history; the complexity and number of theorized causes can be a major cause for confusion. One of the main reasons for this complexity is the long period over which this war’s tension built, beginning with the unification of Germany by Bismarck, and escalating from there on. There is no doubt that Germany's misguided foreign policy contributed to the outbreak of war, however the extent to which it contributed is the contended issue.

Some historians suggest that Germany willed the war and engineered its outbreak, and others even suggest that Germany felt compelled to go to war at that time. However, some suggest that the war was brought about by poor leadership at the time, others argue that the war was brought about by accident - that Europe stumbled into war due to tension between alliance systems. Finally, some historians argue that World War I was the culmination of historical developments in Europe. This argument states that war was inevitable between Austria and Serbia, that imperial expansion by Russia eastward was also likely to provoke war, and that the French were still furious over their loss of Alsace-Lorraine in the Franco-Prussian war.

There was certainly a general rise in nationalism in Europe, which played a major role in the start of the conflict. The war became inevitable when the so-called "blank check" was created when Austro-Hungarian Emperor Franz Joseph sent a letter to German Kaiser Wilhelm II, asking for German support against Serbia. Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg, Kaiser Wilhelm II's Imperial Chancellor, telegrammed back that Austria-Hungary could rely on Germany to support whatever action was necessary to deal with Serbia.

The Alliance System

[sửa]One factor which helped to escalate the conflict was the alliance system of the late nineteenth century. Although there had always been alliances between different European nations, the diplomatic trend during the nineteenth century was to have secret alliances, committing states to defensive military action. These were encouraged by Bismarck who, in the process of unifying Germany, sought to pacify those surrounding states which might proved hostile. Although Germany had originally allied itself with the empires of Austria and Russia at this time, by the beginning of the twentieth century alliances had shifted. Germany found itself allied with Austria-Hungary and Italy, the so-called "Central Powers"; together the countries formed what was known as the "Triple Alliance". Meanwhile, France, desperate for allies after the Franco-Prussian war, had cultivated a friendship with Russia. Great Britain, too, felt isolated in the increasingly factionalised European environment, and sought out an alliance with another of Europe's great powers. This led to the Entente Cordial with France, which was to develop into the "Triple Entente" between Britain, France and Russia.

By 1914 most of the smaller European states had been drawn into this web of alliances. Serbia had allied itself with Russia whilst its enemy, Bulgaria, chose the patronage of Germany. A number of small states maintained their neutrality in this complicated network of alliances. Belgium, for instance, was a neutral state, its independence guaranteed by Britain, France, and Germany.

The War

[sửa]The Schlieffen Plan

[sửa]

The Schlieffen Plan was designed by Field Marshall Count Alfred von Schlieffen, who became Chief of the Great General Staff in 1891 and submitted his plan in 1905. Out of fear of a two front war, which Germany was nearly certain it could not win, it devised the plan to eliminate one of the fronts of the war before the other side could prepare. The plan called for a rapid German mobilization, sweeping through Holland, Luxembourg and Belgium into France. Schlieffen called for overwhelming numbers on the far right flank, the northernmost spearhead of the force with only minimum troops making up the arm and axis of the formation as well as a minimum force stationed on the Russian eastern front. Swift elimination of the French threat would in theory allow Germany to better defend against a Russian, or a British force. However, the British involvement was not looked for under the Schlieffen plan, not at the commencement of action at least.

In 1905 Count Schlieffen expected his overpowering right wing to move basically along the coast through Holland. He expected the Dutch to acquiesce and grant the army the right to cross their borders. Schlieffen knew that navigating around the Belgian fortress at Liege in this way would speed the advance while still defeating the fortress simply by encirclement. Schlieffen retired from his post in 1906 and was replaced by Helmuth von Moltke. In 1907-08 Moltke adjusted the plan, reducing the proportional distribution of the forces, lessening the crucial right wing in favor of a slightly more defensive strategy. Also, judging Holland as unlikely to grant permission to cross its borders the plan now called for a direct move through Belgium but expected the French force to officially invade neutral Belgium first in an attempt to take the advantageous position at Meuse. Moltke's variation called for an artillery assault on Liege, but with the rail lines and the unprecedented firepower the German army brought what he did not expect any significant defense of the fortress.

August 1914: War Erupts

[sửa]On June 28, 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the Austria-Hungary throne, was assassinated in Sarajevo. As a result, Austria declared war on Serbia. Germany declared war on both Russia and France. On August 4, Germany invaded neutral Belgium before the French. This precipitated in Great Britain's declaration of war on Germany.

Enacting the Moltke variation of the Schlieffen Plan, German forces entered Belgium, attacking the fortress of Liege. Although they could not stop the large invading force, Belgian troops fought bravely, and the siege lasted 10 days, arguably upsetting the German timetable and allowing for mobilization of the French and the British Expeditionary forces. During the second half of August, however, a hasty French counteroffensive in Lorraine collapsed, with heavy casualties in the face of German machine-gun fire. French armies fell back in disarray as the Germans crossed from Belgium into France on a wide front.

Keeping its alliance with France, Russia's armies invaded Germany's easternmost province, East Prussia, in August. The German high command dispatched General Paul von Hindenburg to defend the province. Hindenburg took command and defeated the Russians at the Battle of Tannenberg, ending the hope of a Russian advance to Berlin.

The end of August was marked by near-panic in northern France as the German offensive rolled south toward Paris, seemingly unstoppable. On the German side, however, a gap developed between the westernmost army corps, and the rapid advance was exhausting the troops. The French rushed reinforcements from Paris -- some in taxicabs -- to the front, and by the first week of September, amid heavy fighting, the Germans had been halted along the River Marne. This marked the beginning of the static trench lines which would define the front in Western Europe for four years.

1915-1916

[sửa]On February 4, 1915, Germany declared a submarine blockade of Great Britain, stating that any ship approaching England was a legitimate target. On May 7, 1915, Germany sank the passenger ship Lusitania, resulting in a massive uproar in the United States, as over 100 U.S. citizens perished. On August 30, Germany responded by ceasing to sink ships without warning.

The front in France became the focus of mass attacks that cost huge numbers of lives, but gained very little. Britain became fully engaged in France, raising a large conscript army for the first time in its history. 1915 saw the first attacks with chlorine gas by the Germans, and soon the Allies responded in kind. During much of the year 1916, the longest battle of the war, the Battle of Verdun, a German offensive against France and Britain, was fought to a draw and resulted in an estimated one million casualties. On July 1 through November 18, the Battle of Somme, a British and French offensive against the Germans, again resulted in approximately one million casualties but no breakthrough for either side.

1917-1918: Final Phases

[sửa]On February 1, 1917, Germany again declares unrestricted submarine warfare. The Germans believed that it was possible to defeat the British in six months through this, and assumed it would take at least one year for America to mobilize as a result of the actions. Thus, they banked on the hope that they could defeat Britain before America would enter the war.

A mood of cultural despair had settled over much of Europe by this time, as an entire generation of young men was fed into the maw of combat. French armies came close to mutiny in 1917 when ordered into an attack they knew would be hopeless. Germany, blockaded from overseas trade, saw hunger and deprivation among the population, with labor strikes and political discontent growing. Russia underwent collapse, its armies defeated and the Tsar ousted in favor of a liberal-socialist regime.

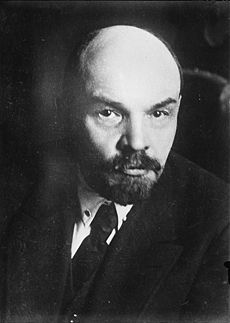

On April 6, 1917, the United States entered the war by declaring war on Germany. This was in part due to the sinking of the Lusitania and the Zimmerman Telegram, which was a ploy to convince Mexico to attack the United States in exchange for the return of Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona should the United States enter the war. From July 31 through November 10, 1917, the Third Battle of Ypres, also known as Passchendaele, resulted in minor gains for the British, but there was still no breakthrough of the well-developed German defenses. During this time, on November 7, Bolsheviks, led by Lenin, overthrew the post-Tsar Russian government.

As a result, in March 1918, the new Russian government, represented by Leon Trotsky, signed an armistice treaty with Germany, removing the eastern front of the war for Germany. On March 21, Germany thus launched what is known as the Ludendorff offensive in the hope of winning the war before American troops arrived. The final German effort, however, fared no better in the end than the previous ones; the Germans pushed closer to Paris than ever before, but by the end of summer they had exhausted themselves against the Allied defenses, now including fresh American armies.

On September 29, 1918, allied troops broke through the German fortifications at the Hindenberg line, and the end of the war came into view. On November 9, 1918, Kaiser Wilhelm II abdicated, and on November 10 the German Weimar Republic was founded. On November 11, 1918, at eleven o'clock on the eleventh day of the eleventh month of 1918, the war ended as Germany and the Allies signed an armistice agreement.

The War in Italy

[sửa]

Italy had been allied with the German and Austro-Hungarian Empires since 1882 as part of the Triple Alliance. However, the nation had its own designs on Austrian territory in Province of Trento, Istria and Dalmatia. Rome had a secret 1902 pact with France, effectively nullifying its alliance. At the start of hostilities, Italy refused to commit troops, arguing that the Triple Alliance was defensive in nature, and that Austria-Hungary was an aggressor. The Austro-Hungarian government began negotiations to secure Italian neutrality, offering the French colony of Tunisia in return. The Allies made a counter-offer in which Italy would receive the Alpine province of South Tyrol and territory on the Dalmatian coast after the defeat of Austria-Hungary. This was formalised by the Treaty of London. Further encouraged by the Allied invasion of Turkey in April 1915, Italy joined the Triple Entente and declared war on Austria-Hungary on May 23. Fifteen months later Italy declared war on Germany.

Militarily, the Italians had numerical superiority. This advantage, however, was lost, not only because of the difficult terrain in which fighting took place, but also because of the strategies and tactics employed. Field Marshal Luigi Cadorna, a staunch proponent of the frontal assault, had dreams of breaking into the Slovenian plateau, taking Ljubljana and threatening Vienna. It was a Napoleonic plan, which had no realistic chance of success in an age of barbed wire, machine guns, and indirect artillery fire, combined with hilly and mountainous terrain.

On the Trentino front, the Austro-Hungarians took advantage of the mountainous terrain, which favoured the defender. After an initial strategic retreat, the front remained largely unchanged, while Austrian Kaiserschützen and Standschützen engaged Italian Alpini in bitter hand-to-hand combat throughout the summer. The Austro-Hungarians counter-attacked in the Asiago towards Verona and Padua, in the spring of 1916, but made little progress.

Beginning in 1915, the Italians under Cadorna mounted eleven offensives on the Isonzo front along the Isonzo River, north-east of Trieste. All eleven offensives were repelled by the Austro-Hungarians, who held the higher ground. In the summer of 1916, the Italians captured the town of Gorizia. After this minor victory, the front remained static for over a year, despite several Italian offensives. In the autumn of 1917, thanks to the improving situation on the Eastern front, the Austrians received large numbers of reinforcements, including German Stormtroopers and the elite Alpenkorps. The Central Powers launched a crushing offensive on 26 October 1917, spearheaded by the Germans. They achieved a victory at Caporetto. The Italian army was routed and retreated more than 100 km (60 miles) to reorganise, stabilizing the front at the Piave River. Since in the Battle of Caporetto Italian Army had heavy losses, the Italian Government called to arms the so called '99 Boys (Ragazzi del '99), that is, all males who were 18 years old. In 1918, the Austro-Hungarians failed to break through, in a series of battles on the Asiago Plateau, finally being decisively defeated in the Battle of Vittorio Veneto in October of that year. Austria-Hungary surrendered in early November 1918.[1][2][3]

The War at Sea

[sửa]

At the start of the war, the German Empire had cruisers scattered across the globe, some of which were subsequently used to attack Allied merchant shipping. The British Royal Navy systematically hunted them down, though not without some embarrassment from its inability to protect Allied shipping. For example, the German detached light cruiser SMS Emden, part of the East-Asia squadron stationed at Tsingtao, seized or destroyed 15 merchantmen, as well as sinking a Russian cruiser and a French destroyer. However, the bulk of the German East Asia Squadron — consisting of the armoured cruisers SMS Scharnhorst and SMS Gneisenau, light cruisers SMS Nürnberg and SMS Leipzig and two transport ships — did not have orders to raid shipping and was instead underway to Germany when it encountered elements of the British fleet. The German flotilla, along with SMS Dresden, sank two armoured cruisers at the Battle of Coronel, but was almost completely destroyed at the Battle of the Falkland Islands in December 1914, with only Dresden and a few auxiliaries escaping, but at the Battle of Más a Tierra these too were destroyed or interned.[4]

Soon after the outbreak of hostilities, Britain initiated a naval blockade of Germany. The strategy proved effective, cutting off vital military and civilian supplies, although this blockade violated generally accepted international law codified by several international agreements of the past two centuries.[5] Britain mined international waters to prevent any ships from entering entire sections of ocean, causing danger to even neutral ships.[6] Since there was limited response to this tactic, Germany expected a similar response to its unrestricted submarine warfare.[7]

The 1916 Battle of Jutland (German: Skagerrakschlacht, or "Battle of the Skagerrak") developed into the largest naval battle of the war, the only full-scale clash of battleships during the war. It took place on 31 May–1 June 1916, in the North Sea off Jutland. The Kaiserliche Marine's High Seas Fleet, commanded by Vice Admiral Reinhard Scheer, squared off against the Royal Navy's Grand Fleet, led by Admiral Sir John Jellicoe. The engagement was a standoff, as the Germans, outmaneuvered by the larger British fleet, managed to escape and inflicted more damage to the British fleet than they received. Strategically, however, the British asserted their control of the sea, and the bulk of the German surface fleet remained confined to port for the duration of the war.

German U-boats attempted to cut the supply lines between North America and Britain.[8] The nature of submarine warfare meant that attacks often came without warning, giving the crews of the merchant ships little hope of survival.[9] The United States launched a protest, and Germany modified its rules of engagement. After the notorious sinking of the passenger ship RMS Lusitania in 1915, Germany promised not to target passenger liners, while Britain armed its merchant ships, placing them beyond the protection of the "cruiser rules" which demanded warning and placing crews in "a place of safety" (a standard which lifeboats did not meet).[10] Finally, in early 1917 Germany adopted a policy of unrestricted submarine warfare, realizing the Americans would eventually enter the war.[11] Germany sought to strangle Allied sea lanes before the U.S. could transport a large army overseas.

The U-boat threat lessened in 1917, when merchant ships entered convoys escorted by destroyers. This tactic made it difficult for U-boats to find targets, which significantly lessened losses; after the introduction of hydrophone and depth charges, accompanying destroyers might actually attack a submerged submarine with some hope of success. The convoy system slowed the flow of supplies, since ships had to wait as convoys were assembled. The solution to the delays was a massive program to build new freighters. Troop ships were too fast for the submarines and did not travel the North Atlantic in convoys.[12][13] The U-boats had sunk almost 5,000 Allied ships, at a cost of 178 submarines.[14]

World War I also saw the first use of aircraft carriers in combat, with HMS Furious launching Sopwith Camels in a successful raid against the Zeppelin hangars at Tondern in July 1918, as well as blimps for antisubmarine patrol.[15]

Science and Technology

[sửa]New Military Techniques and Technologies

[sửa]World War I introduced the first time that total war was employed - that is, the full mobilization of society occurred in participant nations. In addition, it marked the end of war as a "glamorous occupation," showing how brutal and horrifying war could be when fought by industrial nations with mass production of weapons, and mass armies drawn from whole populations.

World War I introduced a number of new technologies and techniques. The outbreak of war took the world from the age of coal to an age where energy was largely derived from petroleum, a much higher-grade fuel source used in many new fighting machines and transport systems on land and sea. The deadliest product of this new industry was chemical warfare, with countless fighting men suffering and dying in gas attacks. Submarines also were used with effect, leading to the advent of depth charges and sonar. Rudimentary tanks and mechanized warfare also entered the battlefield near the end of the war. Finally, the machine gun took its toll for the first time in World War I. All this was aimed at breakthrough in trench warfare, in which both sides would dig deep trenches, and attempt to attack the other side, most often with little or no success.

Society and Culture

[sửa]The Russian Revolution

[sửa]The Russian Revolution marked the first outbreak of communism in Europe. Contrary to popular belief, however, there were in fact two specific and unique revolutions that took place during 1917 - a true Marxist revolution as well as a revolution led by Lenin that was not a true Marxist revolution.

March Revolution of 1917

[sửa]The peasants were unhappy with the czar as a result of losses from World War I, the lack of real representation and the czar's dismissal of the Duma, the influence of Rasputin upon Alexandra, hunger, food shortages, and industrial working conditions.

As a result, on March 8, 1917, food riots broke out in St. Petersburg; however, the soldiers refused to fire upon the rioters. At this time, two forces were in competition for control of the revolution. Members of the Duma executive committee called for a moderate constitutional government, while Soviets, members of worker councils, pushed for revolution and industrial reform.

On March 15, 1917, the Czar attempted to return to Russia by train, but was stopped by the troops and was forced to abdicate.

From March through November, a provisional government was led by Alexander Kerensky, a socialist, and Prince Lvov. However, this government was destined to fail because it took no action in land distribution, continued to fight in World War I, and failed to fix food shortages. General Kornilov attempted a coup, but Kerensky used the Soviets and Bolsheviks to put down the coup. However, this action showed the weakness of Kerensky.

The March Revolution marked the first time that the class struggle predicted by Karl Marx took place. Thus, the March Revolution was a true Marxist revolution based upon the theories of Marx in The Communist Manifesto.

November Revolution of 1917

[sửa]

Vladimir Lenin realized that the time had come to seize the revolution. He authored the "April Theses," in which he promised peace with the Central Powers, redistribution of the land, transfer of the factories to the owners, and the recognition of the Soviets as the supreme power in Russia. In this sense, the November Revolution was led by Lenin rather than being an overall coup by the workers, and thus the November revolution cannot be dubbed a true Marxist revolution.

The Revolution may never have happened had not the Prime Minister of the Time, Aleksandr Kerensky, destroyed the power of authority within the Army and Navy by allowing the Bolshevik and Menshevik committees greater powers. Kerensky effectively disarmed the Man who could have prevented the Revolution ever happening. The man in question, was the Commander-in-Chief, General Lavr Kornilov who attempted to bring to heel the populist Government of Kerensky and instill some authority back in to the state and the Army. Kerensky seized the opportunity to relieve Kornilov of his office and effectively gave the Bolsheviks, namely the Red Guard within the ranks of the Petrograd sailors, a Carte Blanc to take up arms in the so called defense of the Provisional Government. The Army lost its Commander and the streets were handed over to the Bolsheviks.

In March 1918 Lenin established the "dictatorship of the proletariat," adopted the name "Communist Party," and signed the treaty of Brest-Litovsk, withdrawing Russia from World War I.

Civil war raged in Russia from 1918 until 1922, pitting the Reds (Bolsheviks led by Trotsky) against the Whites, which consisted of czarists, liberals, the bourgeois, Mensheviks, the U.S., Britain, and France.

The victorious Bolsheviks acted to eliminate their opposition using secret police groups such as the Cheka, the NKVD, and the KGB. Lenin attempted to maintain Marxism, hoping to reach Marx's state of a propertyless, classless utopia. However, the pursuit of communism generally failed and the economy declined. Accordingly, Lenin enacted the New Economic Policy in March 1921, which compromised many aspects of communism for capitalism's profits.

Modern Art

[sửa]The 1900s led to the creation of the new, modern art movement. Fauvism is a type of modern art that emphasized wild, extreme colors, abstraction, simplified lines, freshness, and spontaneity. Cubism is another form of modern art, which utilizes a geometrical depiction of subjects with planes and angles. The modern art movement arose because, with the advent of photography, art subjects no longer needed to be a realistic portrayal.

Perhaps the most famous modern artist is Pablo Picasso, a Spanish painter and sculptor.

References

[sửa]- ▲ Bản mẫu:Citation

- ▲ Bản mẫu:Citation

- ▲ Bản mẫu:Harvnb

- ▲ Bản mẫu:Harvnb

- ▲ Bản mẫu:Harvnb

- ▲ Bản mẫu:Harvnb

- ▲ Bản mẫu:Harvnb

- ▲ "Coast Guard in the North Atlantic War". http://www.uscg.mil/History/h_AtlWar.html. Retrieved 2007-10-30.Bản mẫu:Dead link

- ▲ Bản mẫu:Harvnb

- ▲ Bản mẫu:Harvnb

- ▲ Bản mẫu:Harvnb

- ▲ "Nova Scotia House of Assembly Committee on Veterans' Affairs". Hansard. http://www.gov.ns.ca/legislature/hansard//comm/va/va_2006nov09.htm. Retrieved 2007-10-30.

- ▲ "Greek American Operational Group OSS, Part 3 continued". http://www.pahh.com/oss/pt3/p23.html. Retrieved 2007-10-30.

- ▲ The U-boat War in World War One

- ▲ Bản mẫu:Harvnb